Anioma in Delta not Igbo but a mix of Yoruba, Bini

Interrogating Ethnic Identity against Language Force Majeure

By Nwankwo T. Nwaezeigwe, PhD August 21, 2025

On Friday the 8th day of July 1983, one of the most respected Supreme Court Justices in Nigeria His Lordship Justice Ayo Gabriel Irikefe delivered the lead judgment in Suit Number: Sc.85/1982 in a protracted land dispute between Ukwunzu an Olukumi (Yoruba) town and Obomkpa an Umuezechime (Bini) town, both currently identified as West Niger Igbo (Anioma) communities in Aniocha North Local Government Area, Delta State. Reading the judgment in part, Justice Irikefe stated:

The traditional evidence produced at the hearing shows that the two communities in this case came into existence as the result of migrations by people either from the ancient Kingdom of Benin direct or from AKURE or IFE in the YORUBA Kingdom through Benin. The respondents herein come under the category of those who came from Benin while the appellants represent the second group. While the Benin immigrants now have Ibo as their sole language, the YORUBA immigrants speak both YORUBA and Ibo. There is evidence that the descendants of the YORUBA immigrants refer to themselves as well as their own brand of YORUBA dialect as OLUKUMI. The OLUKUMI settlements as revealed by the evidence are: UKWUNZU, UGBODU, UGBOBA, UBULUBU, OGODO and IDUMUOGO.

Having arrived so far at this point of our intellectual promenade, it will be apropos to conclude by stating that the old Professor Adiele Afigbo school of thought that centered on reverse migrations being alluded to such movements as the Umuezechime and related eastward migrations no longer subsists in the light of emerging evidence. Such allusion was constructed on speculative historical evidence on the ground that there was no incontrovertible evidence to the contrary.

With the copious evidence of the pre-Oduduwa Igbo aborigines of Igbo-Mokun (Ile-Ife) now emerging, the idea of reverse migrations no longer stands. One of the major reasons for this assertion is the fact that most, if not all the surviving aborigines of West Niger Igbo who were met on ground by later immigrants from east of the Niger claim Benin tradition of origin.

These aboriginal communities include Okwe, Umuezeanyanwu and Umuobi Ugboma both of Umuezenei Quarters of Asaba; Umu Opu Quarters of Akwukwu-Igbo; and Ikelike Quarters of Ogwashi-Uku, among others. So far there are no records or evidence of earlier-than these people migrations westward from east of the Niger.

It is therefore right to state quite emphatically that the aboriginal settlers of Anioma (West Niger Igboland), even though majorly Igbo by ethnic identity, were scions of the West Niger wing of Igbo migrations from the Niger-Benue Confluence region which pitched their terminus at the present Ile-Ife (Igbo-Mokun). This is evident by the characteristic adaptability of West Niger Igbo to the customs and values of their Edo and Yoruba neighbors more than they do with their Igbo neighbors of east Niger.

It is also evident that through centuries or millennia of close interactions with their Edo and Yoruba neighbors, including the Igala to the north, which were occasioned by immigrations, Anioma land evolved into what historians often refer to as ethno-linguistic melting-pot, consequently giving rise to a unique identity within the Igbo-speaking linguistic complex.

This identity constructed on multi-ethnic culturalism and driven by westward historical orientation soon became the subject of identity question, not among Anioma people who fully understand who they are, but outsiders, particularly those from southeast Igboland whose conquering propensity and domineering mentality gave them the cacophonic assumption that common language must always stand for common ethnic identity and common historical origins.

This assumption cannot work for a people whose historical origins cut across such ethnic groups as Igbo both east and west, Bini, Esan, Urhobo, Isoko, Ijon, Igala and, Yoruba. It is a medley of these peoples that today define Anioma identity and further redefining them as Igbo-speaking group, rather than Igbo ethnic group. The Yoruba angle of this identity will serve as an instructive element in this question of identity redefinition.

The British Colonial Government anthropologist Northcote W. Thomas speaking further on the Olukumi in the early part of the second decade of the 20th century wrote:

In the north-west portion of the district two towns, Ukunzu and Ubodu, with an offshoot Ubulubu, are remarkable as being Yoruba islands, which appear to have settled in their present situation perhaps some 700 years ago, and yet, in spite of their isolation, preserve their Yoruba language, known as Unukumi, which resembles the Yoruba of Usehin and Akure, until the present day. In fact, the older people are even now unable to speak Ibo fluently, and it is said that until some 50 or 60 years ago the population was monoglot Yoruba. As far as the customs go, they appear to have entirely assimilated those of the surrounding Ibo, except, possibly, in burial customs.

The foregoing two scenarios— first, a Supreme Court Judgment; and second, an anthropological report by a British Colonial Government anthropologist, clearly sum up the trajectory of the hypothesis on which the title of this paper is rested.

Arising from this hypothesis is the hypothetical question: In the light of their historically established Yoruba ethnic origin, can we rightly refer to the Olukumi as Igbo-speaking group or members of Igbo ethnic group within the geo-political complex of Anioma?

The Olukumi which are collectively known as Odiani Clan made up of six communities as noted in the Supreme Court Judgment are generally classed as part of the Igbo of the West Niger (Anioma), even though their indigenous language has remained for centuries Yoruba, with Igbo as their second language. They equally adopt Igbo names as their personal names, thus making it difficult for outsiders to easily determine their Yoruba root.

His Royal Highness Ayo Isinyemeze, the Oloza (King) of Ugbodu Kingdom and Prince Adebowale Ochei of Ugbodu Royal House in describing the process of their transformation to a bilingual Yoruba community in a traditional Igbo society stated:

We began to acculturate and over time we had adopted largely the way of life of our neighbours. We now bear Igbo names. Me, for instance, my name is Isieyemeze but that’s not Olokumi name, that’s an Igbo name. It is a tribute as it were to my family because, I bear an Olokumi name as a first name. My children all bear Olukumi names. I think there is renaissance, an effort of going back to our roots. So, most of the children being born these days are named Olokumi names. “Outside from that, our dance, dress and food we have basically adopted our neighbour’s lifestyle in those regards. Interestingly, practically everybody here speaks Igbo but only as our second language. Our primary tongue is Olokumi and everybody born here speaks that language.

It is therefore clear from the foregoing that against the erroneous inference of identity crisis being alluded to Anioma people by some historical ignoramuses from southeast, what Olukumi-speaking people are indeed faced with is what could be described as reversed deniable of identity.

Reversed denial of identity in this circumstance occurs when a person who is fully aware of his historical ethnic identity tends to knowingly or unknowingly deny the same ethnic identity in the bid to construct a universal identity with his dominant host communities.

In other words, most Olukumi people deny their Yoruba identity to claim Igbo in one respect, and in another respect deny both Igbo and Yoruba to claim Olukumi identity. This pattern of dual ethno-linguistic identity was well noted by Banji Aluko at Ugbodu. As he narrated:

HELLO, this writer said, while knocking at the door, and a young lady, emerging from the building, replied, ta ni yen? When the writer heard the reply, he thought it was a mere coincidence or that his ears were deceiving him. Of course, he had every reason to be surprised since he was not anywhere near the Yoruba enclave where such a reply can only be anticipated. After all, he was more than 100 kilometres away from the nearest Yoruba community; he was in Ugbodu, a town in Aniocha North Local government Area of Delta State. While trying to decipher why the lady gave such a reply, what further followed put the writer in a more confused position. A girl of about five appeared and said, “mo fe ra biscuit.” Perhaps, the people are part of the Yoruba community living in the town, the writer guessed as he tried to find out from the lady. Are you a Yoruba woman; what is the meaning of ta ni yen?” The writer asked the questions at once. Reluctantly, she answered, “I am not Yoruba, o, I am just speaking my language.” Apparently, she was not unaware of the similarity between her language and Yoruba language. The lady refused to entertain any further question about her language and asked him to go to the king’s palace or to the elders if he wanted to know more about the language.

The Olukumi experience is therefore one of the paradoxes of Anioma identity definition and redefinition within the ethno-linguistic complex of Igbo-speaking peoples.

The second hypothetical question revolves round the subject matter of ethnic identity assertion. In other words, what happens when an Olukumi indigene who speaks Igbo and bears Igbo name says he is not Igbo? Do we consider such claim as identity crisis or identity assertiveness? In other words, does a foreigner who speaks Igbo language automatically becomes Igbo? In the same vein, does an Igbo who is unable to speak Igbo as we have many today, automatically lose his Igbo ethnic identity?

Although under conventional definition of ethnic identity language forms a fundamental aspect, but it does not in its entirety constitute the yard-stick for defining ethnic identity. This explains why it is essential to always speak of Igbo-speaking peoples and not simply Igbo people in academic research. This is because underneath a spoken language are essential characteristic differences in origin, culture, socio-political frameworks, religion and value systems.

Furthermore, a new language can be imposed on an existing one thereby forcing the latter into extinction. An example is Aramaic spoken in the time of Jesus Christ. A new hybrid language could also develop from the combination of existing languages. An example is Swahili spoken in East and Central Africa.

Different ethnic or racial groups could also speak one common language while still maintaining their ethnic and racial differences. Examples include the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa of Republics of Burundi and Rwanda, who are ethnically and racially different but speak the same language—Kirundi/Kinyarwanda.

There are also instances where members of an ethnic group lose their language and adopt the languages of their host communities. Example in this instance are the Ngoni of Malawi, Mozambique and, Tanzania who lost their original Nguni language of Southern Africa following their migrations northwards as a consequence of the Mfecane crisis of the 19th century. They speak the languages of their respective host communities, thereby presenting themselves as members of an ethnic group without a native language. According to Nwankwo Tony Nwaezeigwe in his study of the Ngoni of Malawi:

The Ngoni while retaining substantial traits of their original cultural identity which make their ethnic identity as Nguni ethnographically valid, have virtually lost their original Nguni language, speaking instead the language of their hosts. In other words, the Ngoni is an ethnic group without ethnic language.

Looking at the Northern part of the Nigerian nation, we find the dominance of Hausa language as the main traditional lingua franca, a situation that still leads many people from Southern Nigeria to erroneously classify all Hausa speakers as members of Hausa ethnic group. So it is an error in intellectual idiocy and crass ignorance for anyone to assume, because the people of the present Anioma (West Niger Igbo) speak Igbo they must all be members of Igbo ethnic group.

There are also people who speak the same language, yet bear different names of the same language. The Yoruba spoken today in Southwest Nigeria is spoken in Delta State respectively as Itsekiri and Olukwumi; spoken in Eastern Kogi State as Igala; spoken in Republics of Benin and Togo as Anago; spoken in Republic of Sierra Leone as Aku; and spoken in Republic of Brazil as Nago. In no situation are these differences in names stigmatized as identity crisis.

Daryll Forde and G. I. Jones titled their studies on the Igbo and Ibibio ethnic groups as: “The Ibo and Ibibio-Speaking Peoples of Southeastern Nigeria”, and not “The Ibo and Ibibio Peoples.” These are two difference topical issues which reasons of distinctions are obvious. As they succinctly put it:

Before the advent of Europeans the Ibo had no common name and village groups were generally referred to by the name of a putative ancestral founder. The word Ibo has been used among the peoples themselves as term for contempt by the Riverain Ibo (Oru) for their hinterland congeners…. The Ibo are a single people in the sense that they speak a number of related dialects, occupy a continuous tract of territory and have many features of social structure and culture in common, but they were not formerly politically unified and there are marked dialectal and cultural differences among the various main groupings. Political authority was formerly widely dispersed among a large number of small territorial groups

It therefore follows that language, even though a distinctive feature of ethnic identity could still be absent in the definition of ethnic identity. In fact, the same Forde and Jones went further to state quite convincingly that the West Niger Igbo group (Anioma) “is not a linguistic unit” and that “there are considerable linguistic differences between neighbouring villages.” In their definition of the essential ethno-linguistic features of Anioma people, Forde and Jones stated ipso facto:

The Western Ibo groups appear to be of diverse origins owing to influence from, and possibly admixture with, the Edo-speaking peoples to the west. Some of these contacts probably antedate the rise of the Yoruba influence and the Edo State of Benin, as genuine Edo features, found also among the Urhobo and Isoko, are more widespread than elements, such as titles, derived from Benin. There is also evidence of early contacts with the northern Ibo to the east, particularly Onitsha and Nri. Benin features, especially chieftaincy (Obi) and title systems are characteristic only among the Northern Ika. Southern Ika contacts are likely to have been greater with the Urhobo. The Riverain Ibo are the most heterogeneous, their diverse dialects being said to contain elements derived from the Ijaw (to the south) and the Igala (Idah) to the north, a likely consequence of their position along the Niger and the history of their movements.

It is therefore a fortuitous act of moronic ignorance for anybody to think of political unity between Anioma people and the Igbo of Southeast based solely on the dominance of one common Igbo language. Indeed, outside this often over-rated integrative force of common language, both groups lack commonality in fundamental factors or features of group integration.

From settlement patterns, through political and social structures to war, religious and economic traditions, Anioma people have more in common with their Edo neighbors to the north, west and south, than their Igbo-speaking neighbors to the east. These cultural elements, including the cosmological aspects even though seemingly Igbo in features cannot be said to have been derived from the Igbo of southeast, rather might have been derived from the original Igbo cultural elements of the ancient Igbo settlement of Igbo-Mokun (present Ile-Ife).

Northcote W. Thomas was on the right path when he reported in the early part of the 20th century the distinction between Anioma people and their southeast Igbo neighbors: “As regards customs, it is clear that the Niger is a far more important boundary than the frontier between languages. The marriage customs on the Asaba side are completely different from those on the east of the Niger.”

Thomas went further to elaborate on this distinctive character in the following words:

In many respects the people of the Asaba side differ very considerably from the Ibo of the Awka district and apparently, so far as my observation goes, from the majority of the other Ibo also. This is true, not only with regard to custom, but more especially in respect of their traditions. East of the Niger, with the exception of the town of Aguku, it was comparatively rare to find any historical traditions, and, as was pointed out in the report, the town of Aguku occupies an exceptional position, and may possibly be of different origin, for they speak of the people round them as Ibo, precisely as the Asaba people refer to the people on the other side of the Niger as Ibo, and precisely as the people of Onitsha Mili, who originally came from the Asaba side, refer to the people east of them as Ibo.

For instance, the same compact pattern of settlement without walls and fences around houses runs all the way from Yorubaland through Edo to Anioma on the Niger. People live together as members of one family. On the other hand, across the Niger to the east a different pattern of dispersed form of settlement with wall barriers separating one house from the other.

There is also the question of economic orientation which widely differentiates both sides of the Niger divide. Among Anioma people it is very rare to see men engaged in retail commercial activities, which is the foundation of the economic activities of the Igbo men of Southeast.

The business of selling and buying under retail commercial activities in markets is reserved for Anioma women. Indeed, it is rare to see any Anioma man till date rubbing shoulders with women in markets in the name of selling goods. It is even rare to see an Anioma man going to the market to buy food items, unless such items are for spiritual purposes that require a man to purchase personally. If a man has no wife then it is customary that he delegates such duty to another woman, possibly his relative or neighbor.

All the markets in Anioma (West Niger Igbo) are under the full control of women headed by the Omu. Northcote W. Thomas noted this in the following accounts:

This superior organisation on the Asaba side is evidenced in another direction by the fact that the women, more especially with regard to the markets, are under the control of one or more dignitaries of their own sex. Nearly everywhere in the Asaba district the markets are presided over by a functionary known as Qmu, who has disciplinary powers over offenders in the market, and can punish women for leaving their own markets for those of neighbouring towns, for charging more than the customary prices or for infractions of ritual prohibitions. In addition, they collect dues of various kinds, more especially for purposes connected with religion or magic, such as the making of the market medicine.

Socio-political structure— kingship, Onotu/Olinzele, gerontocracy, war tradition, age-grade organizations, burial and marriage customs, are quite distinct from what are obtained among the Igbo of southeast. Anioma war tradition which is akin to Bini war tradition has a defined fighting age popularly known as Otu-Okwulagwe. There is also the cult of warriors known as Ogbuu or Otu-Agana. All these are distinctive features of Anioma people which are absent among the Igbo of Southeast.

We need not go into the subject of differences in ethical orientation and why the Igbo of southeast have proven to be a problem unto themselves and unto associated Igbo groups like Anioma. Recently, a once very close friend of mine from Nnewi in Anambra State named Dr. Chukwukadibia Odunukwu wrote to me in response to the third essay in this series:

The land I have in Ibuso is mine and I have certificates of occupancy and a competent judgment against the children of the person I acquired the land from. I am a southeastern Igbo. More than 50% of Asaba land is now owned and occupied by southeast Igbo citizens. Nothing anyone can do about it.

A responsible son of Anioma who is conscious of his historical identity as Igbo-speaking would not make such insane statement of arrogance plaited in pitiable foolery before his host or somebody under whose traditional custody his landed property is domiciled. Who knew the sort of such statement that led to the abandoned property saga in Port Harcourt during the Nigerian civil war or, why there is current onslaught against Igbo presence in Lagos State.

Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu killed Sir Ahmadu Bello no doubt. But there were certain actions deemed as mockery and provocative taken by the Igbo of Southeast after the death of Sir Ahmadu Bello. First was the music record label that depicted Sardauna as crying like a goat. Second was the Drum Magazine cartoon depicting Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu placing his one leg on slain Sir Ahmadu Bello with rifle in one hand; third was the infamous unification decree by Major General Aguiyi-Ironsi, which spirit equally guided the call to unify Anioma with Southeast geo-political zone; and finally, the refusal to court-marshal the January 15, 1966 coup plotters.

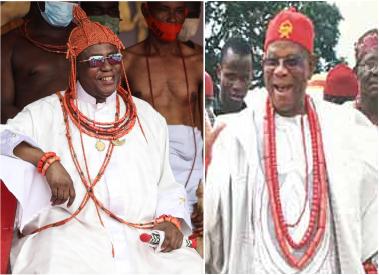

Again, among the Igbo of Southeast, the abuse, disrespect and destruction of their customs and tradition are proudly taken as the instruments of their modern-day acculturalization. We equally noted some social media pro-Igbo touts from southeast insulting revered traditional rulers of Anioma for taking their justified position on the question of their ethnic origin and identity. Anioma people cherish and respect their traditional institutions and thus would not wish to politically integrate with those who have no such respect for their own and other people’s customary values and traditional institutions.

Equally notable among southeast Igbo is the fact that such a revered traditional institution as traditional rulers lacks the requisite protective customary and traditional sanctions and is therefore quite often treated with ignominy. Indeed, it is impossible to see any son of Anioma engaged in the embarrassing business of Eze-Ndigbo in foreign lands. A responsible Anioma son knows that claiming to be a king in a foreign land when even his family is not qualified to bear a common chieftaincy title is a serious taboo.

These are some of the issues that go beyond common language and which make political integration between Anioma and Edo people more workable and appropriate than with the Igbo of Southeast. An Edo man knows the values of his customs, tradition and identity as much as an Anioma man knows in the same manner. Common value orientations serve more to forge a sense of unity than the mere speaking of common language.

These further explain why Anioma people see themselves more through the looking-glass of their Edo-driven ethnic identity of “Ika” and “Oru”, than the globalized Igbo identity. It is in the light of these cultural variables in relation to the Igbo of Southeast that Anioma people, while accepting the umbrella of Igbo-speaking groups, prefer to be culturally and ethnically defined as “Anioma.” The Isoko did the same in 1959 from the body of Urhobo ethnic group and thunder did not descend from Heaven on anybody.

(SPECIAL NOTE: Following popular requests to transform these series into a reference book form, I am humbly requesting sponsors and support from willing patriots to indicate their interest through the e-mail contact below).

Dr. Nwankwo T. Nwaezeigwe is the Odogwu Ibusa & President, International Coalition against Christian Genocide in Nigeria (ICAC-GEN). He was formerly Director, Centre for Igbo Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He lives in exile in Manila, Republic of the Philippines.