The meaning of Mother Tongue

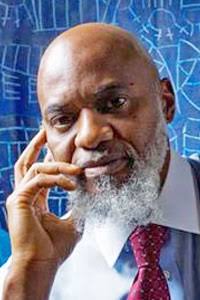

By Prof Moyo Okediji

The first time I saw a white person, I was almost four years old.

My father was a teacher at the Divisional Teacher Training College, Ile-Ife—a Grade 3 teacher-training school.

We lived on the college campus, an exceedingly beautiful place on the outskirts of Ile-Ife, then a relatively small, sleepy town in the 1950s and 1960s.

My recollection of that campus is a memory of flowers blooming throughout the year: green, manicured lawns; large fruit trees—especially the magnificent kolanut trees, their long branches heavy with thick foliage—and the slim cocoa trees, which carried their pods proudly around their bodies, like multiple breasts.

I frequented these plants that grew wild on the campus. To my child’s eyes, kolanut and cocoa seemed to produce similar pods.

You break the pod and find the nuts coated with sweet, succulent flesh. I would snack on that natural sweetness. The nuts beneath it are bitter, and if you eat too much of the sweet flesh, you get a tummy ache.

Some of my father’s colleagues and their families also lived on the campus, but there were no more than ten families on that large ground, bordered by a thick forest—home to wild animals that sometimes strayed into our paths.

The implication was simple: I was by myself most of the time, exploring alone, tasting fruits and seeds without much supervision.

In the evenings, my father and I would take a stroll. He said we were discussing “very important topics,” whatever those might be, and I would tell him what I had been up to all day.

By four, I was already reading and writing. I could read newspapers—Yoruba and English—which my father received regularly.

At first, I was merely mimicking him. He would sit in the living room, looking serious as he went through the papers, while my mother cooked dinner in the kitchen.

I loved the way he read: pausing now and then to make an occasional comment to my mother about what he had just seen.

He seemed to take these printed things quite seriously, but my mother would answer with little more than a grunt—monosyllabic responses, half-amused, half-busy.

I wanted to know what he was reading that was so serious. So one day, as soon as I was old enough to put sensible sentences together, I asked, “Bàámi, teach me how to read your newspapers.”

That was the beginning of my studies.

We began with Yoruba newspapers. It was easy. I quickly got the trick.

What was difficult were the English-language newspapers. One had to understand English first—and I spoke no English.

“Bàámi,” I implored him, “Òyìnbó ni kí ẹ máa sọ sí mi,” meaning, “Dad, why don’t you speak to me in English?”

That was the beginning of my English lessons: my mother spoke to me in Yoruba, my father in English.

I gradually began to build my vocabulary, but it was slow and painfully hard progress.

Not too far from the college campus was the Seventh-day Adventist Mission, with what was known then as a Modern School, and the only hospital in town, together with a nursing school.

I had never been to the Mission campus, because it was far beyond my plant-browsing range.

One evening, my father extended our stroll beyond our usual boundary, toward the Seventh-day Adventist Mission.

Lo and behold, a white man was strolling in our direction with a boy—presumably his son—about my height. They seemed to have emerged from the campus of the Seventh-day Adventist Mission.

I recognized them immediately. I had seen white people in books and in newspapers. “Bàámi,” I said excitedly, “look—Òyìnbó!” I pointed.

My father told me it was rude to point at people. So, I dropped my hand and we kept walking until we reached the man and his son.

The two adults exchanged pleasantries using vocabularies well beyond my capacity. What surprised me was the boy. He could not have been older than I was, yet he spoke English fluently and spoke easily with my father.

All I could do was smile.

But inside I felt ashamed of myself: I could not speak English, and this white boy could. I did not even understand what he was saying.

We continued our stroll, and the Òyìnbó and his son went their way.

“That boy is really smart,” I said. “He spoke such good English—and I couldn’t. I didn’t even understand what he was saying. How did he get so good so quickly?”

My father laughed. “I bet that boy doesn’t understand a word of Yoruba—which you speak fluently.”

His response shocked me. I had assumed everybody was born speaking Yoruba, and then learned English later.

“What do you mean he doesn’t speak Yoruba? He is as tall as I am.”

My father laughed even louder, then explained carefully how languages operate.

“You naturally learn the language of your parents,” he said. “You don’t have to learn it. Any other language, you must learn to speak.”

I was flabbergasted. “Really?”

“Yes,” Bàámi continued. “He naturally acquired English from his parents, just as you naturally acquired Yoruba. To understand Yoruba, he would have to learn it—just as you are learning English.”

I heaved a sigh of relief.

“I will teach him to speak Yoruba,” I said, “and he will teach me to speak English.”

“Fair bargain,” my father reassured me, as we strolled back home.

I was quite happy with myself., saying, “I will tell Maami I saw Oyinbo today.”