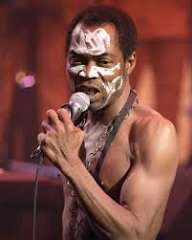

The First Visit of Fela Anikulapo Kuti to Great Ife

By Prof Moyo Okediji

The University of Ife professors who agreed to share the high table with Fela—on that fateful day in 1973—should have known it wasn’t going to end well for them.

The Oduduwa Hall, where the event took place, was bursting at the seams with spectators—packed like a Roman gladiator amphitheater.

That symposium gave me my first opportunity to see this legendary musician, whose fame (or notoriety) was already universally acknowledged.

By the time he visited Ile-Ife, he had released some timeless songs, including:

- 1971: “Let’s Start” (with Ginger Baker)

- 1972: “Shakara,” “Roforofo Fight,” “Afrodisiac”

- 1973: “Gentleman,” “Alu Jon Jonki Jon”

I was a fan of Fela’s music—something my father strategically frowned upon, because everyone knew Fela openly smoked marijuana, a substance most people feared.

My father, who I’m sure knew better, would argue with me:

“Is that music? Shouting ‘Ha, ho, hu, hey’ instead of composing fine music with enjoyable lyrics. He is always criticizing authority. Does he want to cause confusion?”

My father was a pianist, and I was certain he enjoyed Fela’s compositions—as well as Fela’s critical stance against authority.

After all, as a writer, my father wrote the classic Yoruba play about the uprising of the working class, titled RẸ́RẸ́ RÚN.

Still, he frowned upon Fela’s use of marijuana and worried about Fela’s influence on young people—that the habit might lure them into that disposition.

Most university students at the time could separate their love for Fela’s new brand of music and his activism from his use of marijuana.

We went in droves to listen to his lectures because we approved of the political message he was delivering to the youth, at a period when we were beginning to suspect that the educational system designed for us was a trap—snaring us within a neocolonial mentality.

Fela was the only person who articulated that message with such clarity.

Our professors at the university prided themselves as upholders of that neocolonial system.

They were training us to replace them when they retired.

Fela was aware of the role of Nigerian universities in constructing and accepting this architecture of oppression.

But many of us were too young and naïve to understand how to think beyond the box of the neocolonial university system.

Fela was the only public figure who deconstructed the system so clearly—but he was also a musician who charged money for his performances.

Most of us had no money to listen to him live, and we took solace in his recorded music.

It was therefore a great opportunity to listen to Fela for free at Oduduwa Hall on that day in 1973.

Fela was billed to speak alongside three other radical professors on campus. The only name I can recall among them is Dr. Segun Osoba.

Dr. Osoba was a Marxist scholar—a fire-spouting socialist who taught sociology. I never missed his public lectures.

I went early to the auditorium to ensure I got a good seat.

But Fela did not show up, and the scheduled start time was fast approaching.

We expected him to arrive from Lagos—by road, of course.

The other members of the panel were already seated, and the moderator was getting fidgety.

Suddenly, there were noises and shouting from outside.

Then Fela entered the hall, carried on the shoulders of his fans down the aisle to the high table.

He was dressed in his signature tight long-sleeve shirt and tight pants, sewn from the same fabric and elegantly adorned with embroidery.

He raised both hands in his signature Black Power salute—not smiling, his face calm but serious.

He took his seat among the professors, who already looked uncomfortable with the hero’s welcome he was receiving.

The speakers were to have fifteen minutes each, followed by fifteen minutes for questions and comments from the audience.

Dr. Osoba went first. He spoke of social inequality and quoted Marx copiously, presenting Marxism as the only theory that could dismantle the contradictions inherent in the Nigerian economy.

Barely had Osoba sat down when Fela stood up and took over the microphone.

“I have not driven here all the way from Lagos—together with my beautiful queens—to speak for fifteen minutes,” Fela began. “What this professor just said is total bullshit. You university lecturers are full of crap, meeeen!”

Fela was pulling no punches.

“You wear your coat and tie and come and spew out colonial mentality. You need to calm down and relax.”

Someone at the back of the hall started clapping, and soon others joined in.

Fela continued: “You guys should stop this Marxism nonsense—importing foreign ideologies you don’t understand. You are confusing our youths with kòlò mentality!”

The professors at the high table looked agitated.

Then he went further:

“First you need to remove your coat and tie and learn to f—ck! When last did you f—ck?”

He turned to Dr. Osoba. “When last did you f—ck your wife?”

The poor professor looked furious, his brows furrowed.

“I f—ck my queens five times daily,” Fela announced. “Yes—five times. It gives me energy to create and….”

Dr. Osoba and the other professors rose from their seats and stormed out of the hall.

The audience went wild with applause.

Fela continued for the next two hours, moving from one topic to another as the crowd hailed him.

I was thinking: “Five times a day? Lucky bastard! I had never even done it once in my entire life….”

When Fela was done, his queens brought food and drinks to him at the high table.

We were all asked to leave, to give him space to “meditate.”

We reluctantly trooped out of the hall, reflecting on the remarkable experience we had just witnessed.